Free Workshop | Farm Marketing Meets AI: Learn ChatGPT Workflows for Busy Farmers

.webp)

+1 (855) 699 1026

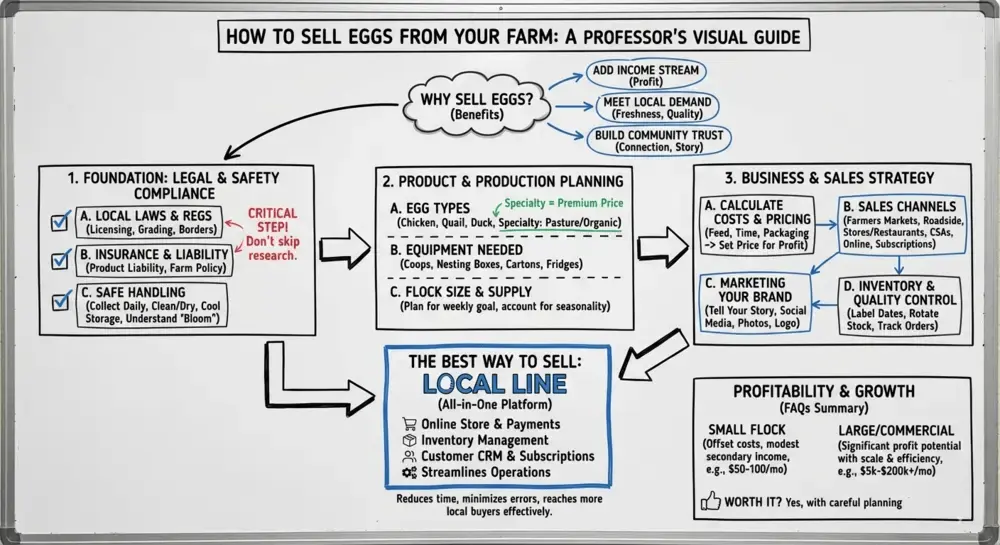

Have you ever thought about turning your farm’s flock of chickens, ducks, quail, or other birds into a reliable source of income? For many farms, selling eggs is one of the most practical ways to add a new revenue stream while making use of animals you already raise.

Whether you manage a small farm with hundreds of birds or keep a modest backyard flock, selling eggs can bring both profit and personal satisfaction. It’s a chance to meet growing consumer demand for fresh, local food and to build relationships with customers who care about quality and sustainability.

But there’s more to it than simply collecting eggs and putting up a “for sale” sign. Legal regulations, food safety standards, pricing decisions, and marketing strategies all play a part in making your egg business successful.

This guide will help you navigate the essentials of selling eggs, so you can turn your flock into a thriving business, whether you’re looking to boost your farm’s bottom line or start a profitable side hustle.

Selling eggs is more than a business, it’s a way to connect with people who care deeply about where their food comes from. Many customers are looking for:

When you sell eggs, you’re not just selling food. You’re selling trust, quality, and a story about how your animals are raised.

Beyond the moral and community benefits, selling eggs can help offset feed costs, generate profit, and justify the time and energy you put into your flock. For many, it’s the first step into broader farming or homesteading ventures, opening doors to selling produce, meat, or value-added products.

One of the biggest mistakes new egg sellers make is skipping the legal research. Rules about selling eggs vary dramatically depending on:

For example, in some US states, you can sell small quantities of eggs directly from your farm without a license, as long as they’re labeled properly. In other states, even small producers must grade and wash eggs before selling them to retail stores. In Canada, selling eggs across provincial lines triggers strict Canadian Food Inspection Agency rules that require grading and inspections.

Start by contacting your local agriculture department or health authority. A quick phone call can clarify whether you need inspections, special labeling, or storage protocols. It’s always better to ask upfront than face fines or be forced to shut down later.

Even the smallest egg seller should consider insurance. Selling food comes with risks, from accidental contamination to someone cracking a tooth on a hidden eggshell fragment.

Insurance protects both you and your customers. Policies to explore:

Talk to an insurance agent who specializes in agricultural businesses. The right policy can save you from financial disaster.

Food safety is critical. Even if your birds look healthy, eggs can carry bacteria like Salmonella. Safe handling protects your customers and your business reputation.

Understanding the bloom is key. The bloom is a natural coating that protects the egg from bacteria and moisture loss. Many small farms in the US and Canada sell unwashed eggs directly to consumers to preserve the bloom. However, retail stores often require washed eggs for safety reasons.

Not all eggs are created equal, nor are they equally profitable. You might have chickens now, but there’s growing demand for other types of eggs:

Specialty eggs like organic, pasture-raised, or omega-3 enriched can command premium prices. For instance, pasture-raised eggs often sell for double the price of standard cage-free eggs because consumers associate them with better animal welfare and richer nutrition.

Consider these questions:

For example, quail eggs are popular in restaurants and specialty markets but require specific housing and care. Duck eggs sell well to bakers due to their higher fat content. But duck housing needs extra water management, and ducks often lay eggs in messier conditions.

Selling unique eggs can set you apart, but only if your market is ready to pay the higher price.

Good equipment can make or break your egg business. While you can start small, investing in solid tools saves time and headaches.

For larger operations, you might consider:

Quality equipment keeps eggs clean, protects your flock, and ensures your products look professional.

More birds mean more eggs, but also more feed, labor, and costs. Plan your flock size based on:

A single hen can lay roughly 250–300 eggs per year. If you want to sell 20 dozen eggs weekly, you’d need at least 40–50 hens, accounting for off-lay times and older hens slowing production.

Also consider breed characteristics. Some heritage breeds lay fewer eggs but attract premium buyers for colorful shells. Commercial hybrids may lay more reliably but command lower prices.

Track egg counts daily. Knowing your production trends helps avoid overpromising or wasting surplus.

You can’t run a business on guesswork. Calculate your costs so you know how much you need to charge to sell your eggs for profit.

Suppose you sell eggs for $5/dozen but spend $3.80/dozen on feed, packaging, and time. Your profit is only $1.20/dozen, and that’s before any surprises like vet bills.

Check what similar sellers charge at:

Specialty eggs like pasture-raised often sell for $7–$10/dozen in urban areas, while regular farm-fresh eggs might be $4–$6/dozen.

Don’t be afraid to charge what your product is worth. Customers often pay more for transparency and quality.

Your sales channels can make or break your egg business. Different outlets suit different flock sizes and business styles.

Marketing isn’t optional, it’s what keeps your customers coming back.

Start with your story. Why did you start keeping chickens? Are your birds pasture-raised? Do you use heritage breeds? People love buying from someone they know and trust.

Even a small social media presence can create loyal followers who look forward to your posts and become regular buyers.

Running out of eggs, or worse, selling old eggs, can damage your reputation. Set up systems to keep things organized:

Learn more about Local Line’s farm inventory management software.

The best way to sell eggs is through Local Line. Local Line is an all-in-one sales platform built for farmers and food producers who want to sell their products efficiently and professionally. It gives you everything you need to manage your egg business, including:

Instead of juggling spreadsheets, messages, and manual orders, you can handle everything in one place. Local Line saves time, reduces errors, and helps you reach more customers who care about buying local.

Start selling eggs online and locally with Local Line - it’s easy to get started!

Begin small. Check local laws, keep your operation clean and organized, and find local markets where customers value fresh, local eggs.

Usually, yes. Licensing requirements vary. Contact your agriculture department or health authority.

It depends on local laws. Some areas require washing for retail sales; others allow selling unwashed eggs directly to customers.

Farmers markets, roadside stands, local grocers, restaurants, CSAs, and online platforms.

Depending on quality and region, prices range from $4 to $10 per dozen, with specialty eggs fetching premium prices.

Possible but risky. Shipping laws vary, and breakage is a real concern.

Usually, yes. Labels often require collection dates, farm details, and safety information.

Refrigerated eggs stay fresh for several weeks. Always sell your oldest eggs first.

Washed eggs lose the bloom that protects freshness. Some regions require washing for retail sales; others prohibit it for direct sales.

Possibly. Many farm expenses can be tax-deductible. Consult a tax professional familiar with agriculture.

Yes, if you already keep chickens and have surplus eggs. Selling to neighbors or at farmers markets can offset feed costs and provide $50-100 monthly income for a small flock. Large commercial operations (10,000+ hens) can generate $5,000-25,000 monthly, while industrial farms (100,000+ hens) may earn $50,000-200,000+ monthly.

Selling eggs is marginally profitable for small operations. Each hen costs $20-40 annually in feed but can generate $80-150 in egg sales. Expect $2-4 profit per hen per month after expenses.

For large commercial operations (10,000+ hens), monthly profits can range from $5,000-25,000 depending on scale, efficiency, and market contracts. Industrial egg farms with 100,000+ hens may generate $50,000-200,000+ monthly profit through volume, automated systems, and wholesale contracts, though they require significant capital investment and face higher regulatory compliance costs.